|

Treatment on Rongelap, Utirik: Callous, Condescending.

Marshalls Medical Program . . . Disregarding Potential Danger, Food Declared Safe.

By John Hanna, Special to The Bulletin.

Back in March 1974, owing to a series of fortuitous circumstances, I was signed on board a US Army landing

craft, LCU-26, as a civilian crew member. The vessel's mission was to transport members of the annual Atomic Energy

Commission's (AEC) medical survey team to the atolls of Utirik, Rongelap and Bikini, located in the northern Marshall Islands.

Each year, similar teams are dispatched from the states to monitor the inhabitants of these remote islands to see how much

radiation has been absorbed since the last AEC visit. The peoples of Utirik and Rongelap in particular, were exposed

to severe radioactive contamination.

What little I'd heard up to that point, regarding these islanders, was insufficient to prepare me for what

I was soon to experience first hand. On Utirik, the first atoll we were to visit, I was immediately aware of a strong undercurrent

of resentment that the local people projected towards the medical survey team. Although the island was beautiful in

every way, I senced that all was not as idyllic as it appeared. Later, upon arrival at Rongelap, I experienced the same

ominous sentiments. It was clear that these people were not only fearful but also they felt they were being exploited.

After spending only six days amongst the people of Rongelap, I shared their feelings. In light of my observations, this

conclusion was inescapable.

On Rongelap, the first impression prior to landing was that the island was poor. In comparison to

Utirik, there were no freshly painted outriggers to be seen hauled up on the coral beaches. When our landing craft drew

up to the settlement, the islanders on shore stayed in small isolated groups - their demeanor and facial expressions

relayed the same feelings of resentment I had sensed at Utirik - but here the feeling was stronger. There was little

attempt to hide their rancor. On the beach, a few elders greeted the survey team's director, Dr. Robert Conrad from

the Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York state. There was the traditional leis, but it was a cool reception in

comparison to Utirik.

In the coming days, I made the acquaintance of many of the people of Rongelap. The hospitality I enjoyed

was markedly warmer than the AEC people were experiencing. I was glad not to be identified as a member of the survey

team. For them, the islanders openly displayed their feelings of distrust, fear and knowledge of having been betrayed.

Islanders Suffer Acute Radiation Poisoning

Although the AEC removed the 82 inhabitants of Rongelap two days after the blast in 1954, the acute stages

of radiation poisoning became apparent almost immediately.

| A frightened Rongelap woman gets tested |

|

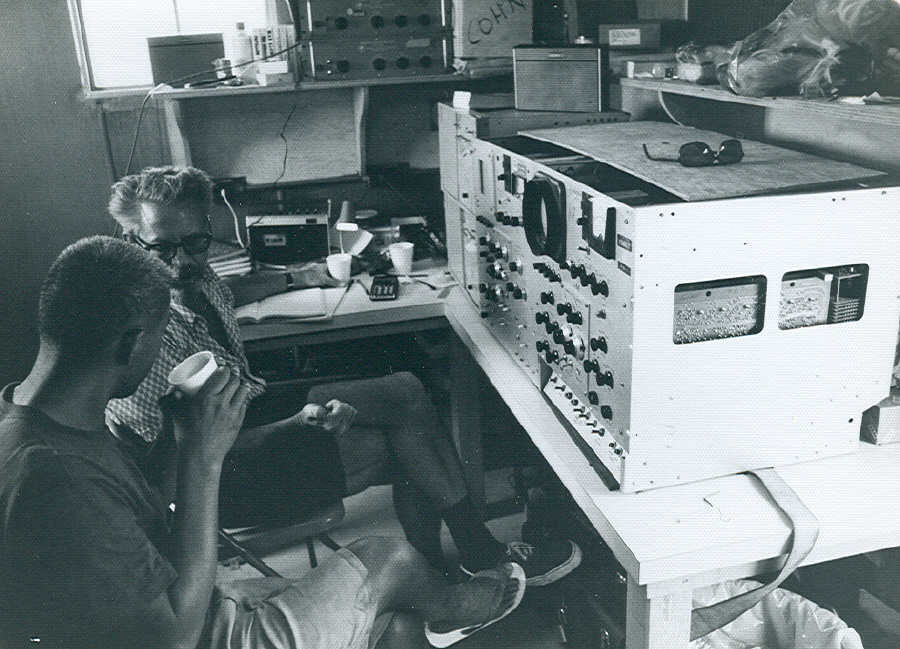

| radiation levels are recorded |

| An AEC technician and LCU-26 crewmember observe |

|

| instrument readings on human guinea pigs |

Nelson Anjain, a resident of Rongelap, described the day of the bomb blast: "Something very strange happened.

It looked like a second sun was rising in the West. We heard noise like thunder, we saw some strange clouds over the

horizon and in the afternoon, something began falling from the sky upon our island. It looked like ash from a fire.

It fell on me, it fell on my wife, it fell on our son. It fell for twelve hours." Now, Nelson, his wife, and two

other sons who were not yet born at the time of exposure, all have had their thyroid glands surgically removed. Nelson

Anjain says that 40 of his people have undergone surgery for cancer.

Perhaps all this suffering and death that has occurred, including suicide, may have been avoided by not

allowing the people to return to Rongelap. But in July of 1957, the AEC states that "in spite of slight lingering radioactivity"

Rongelap atoll is safe for habitation. The people returned to Rongelap from Majuro Atoll, after a three year excile.

Four years later, the AEC reported that the people's body burden of radioactivity rapidly increased.

In spite of these findings which were later corroborated by an independent Japanese medical survey team,

the people of Rongelap were never again evacuated. The only preventative measure taken by the US government was to bulldoze

the irradiated topsoil into the ocean. And, through some bizarre line of reasoning, apply new topsoil from West Germany!

Clearly, then, the Rongelap islanders had every right to display such strong resentment at the time of my visit.

AEC Gift to Rongelap: Stale Food

What particularly disturbed me was the insensitive and condescending attitude of some of the AEC personnel.

On the day of our arrival, after the official greetings were enacted, a member of the AEC team instructed me to gather up

all the week-old stale sweet rolls from the ship's mess room and take them ashore in a large cardboard box to be distributed

to the children who were gathered on the beach. The gesture might win the trust of the young who were so obviously awed,

if not frightened by the yearly test procedures they're submitted to. The AEC member reasoned that, since the rolls

were no longer fit for our consumption, this offering presented no loss to the ship's food supply.

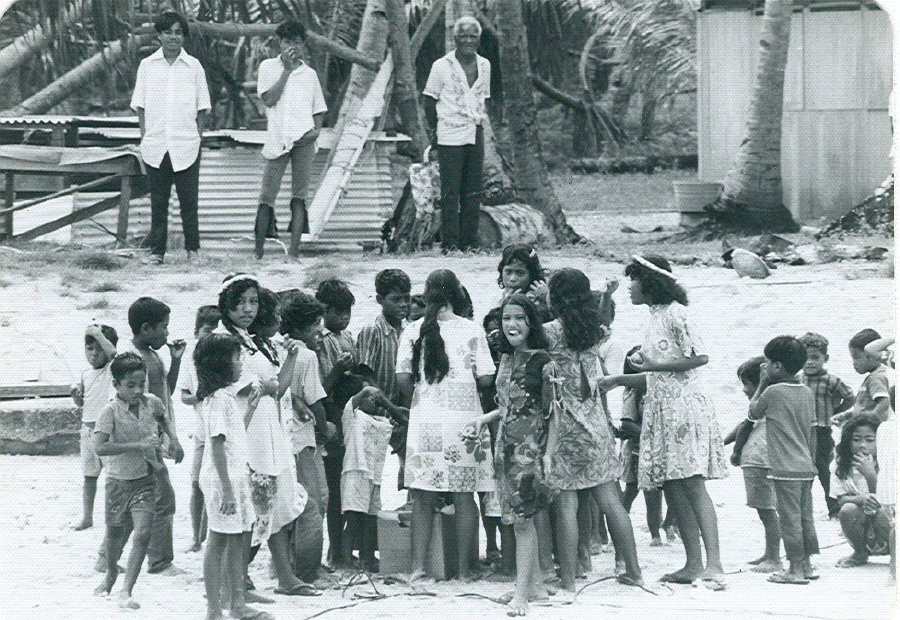

| Children gather around a box of stale sweet rolls |

|

| Good enough for the little patients, says AEC member |

Another shabby incident stands out in my mind as well. The AEC wanted to offer a token gift by presenting

a local fisherman with a small gimballed compass for his boat. However, it was discovered that the dampening fluid that

is normally found in all such compasses had leaked because the compass was defective. Rather than abandon the idea of

offering the compass as a gift, another crewmember and myself were told to fill the compass with water and repair the crack

so the presentation could be made anyway. I submitted to the AEC team member, that without the proper fluid, the compass

would be untrustworthy for navigational purposes at sea and that the water would eventually evaporate rendering the compass

useless altogether. To this, the man replied, "So what? It's the gift that counts, right?" The repair job

was make-shift at best and the compass was awarded to the unsuspecting fisherman with a great show of ceremony.

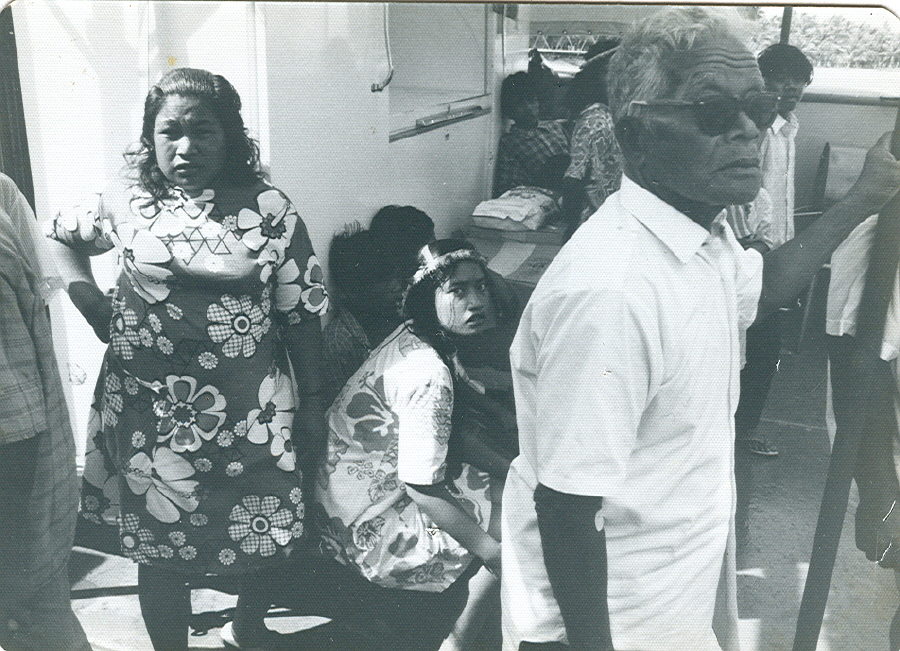

| Mistrust and fear is seen on the islanders' faces |

|

| Rongelap people line up for on-board radiation testing |

In the evenings, it was announced, there were going to be movies. Three films in all on successive

nights. The entire island population was on hand at each occasion. But the choice of films perplexed me.

For one thing the pictures were quite old. The color and the subject matter was unrealistic and wholly unedifying.

First, there was an old Alan Ladd shoot-'em-up with a good amount of gratuitous violence. The second night was an outdoor

"sportsman" type documentary filmed in the Alaskaan wilderness where great white hunters shot down mountain sheep and grizzly

bears, not for food, but for trophies. The last film was an animated cartoon that was so lackluster, I can't recall

its content at all. With all the great films to choose from in the world, the AEC had picked three of the most unremarkable

films I'd ever seen. I thought, what an impression must these people have of American society and culture after seeing

these movies?

Disregarding Potential Danger, Food Declared Safe

Two days prior to our departure, Dr. Conrad made an announcement to the islanders. In essence, he

said: The United States was going through an economic and energy crisis. Therefore, the American people could no longer

afford to feed the people of Rongelap as had been the case these past twenty years. Now, the people of Rongelap would

have to feed themselves. The AEC has determined that the locally available food poses no health hazard. The coconut

crab is also considered safe for the islanders' consumption. To prove this, there will be a luau the evening prior

to LCU-26's departure for Bikini Atoll. We, of the survey team, will eat coconut crab at this luau to prove this is

now safe.

In the past, the coconut crab (which is a large, land dwelling crab) had been singled out as being particularly

radioactive and that the islanders should, at all cost, avoid eating them. This was due to the coconut crab's habit

of ingesting its molted exo-skeleton, as it grows larger. The exo-skeleton contains excessive amounts of strontium-90

which is taken in to living organisms as if it were calcium. By eating its own exo-skeleton, the crabs retain high concentrations

of radioactive isotopes and this in turn is passed on from one generation to the next. Hence, some of us were surprised

to hear Dr. Conrad's announcement that the ban on eating coconut crab was being lifted.

| John Hanna holding a medium-sized coconut crab |

|

| The crab has high concentrations of strontium-90 |

The following day, a curious AEC tecnician and myself, captured a coconut crab in the bush. The crab

was placed in the whole body counter - a sensitive electronic device that records the amount of radiation taken into the human

body. The crab, it was found, was more radioactive than the radioactive liquid used to zero in and calibrate the components

of this sophisticated measuring device. It was then I realized that the AEC was using the people of Rongelap and Utirik

as human guinea pigs. It didn't require a degree in nuclear physics to understand that if these crabs are eaten on a

regular basis, one would eventually become ill and perhaps die as a result.

The luau was held that evening. I watched as the AEC team members placed portions of cooked coconut

crab on their paper plates. I took a couple of bites. The crab meat was delicious. I could see why it's

considered a delicacy by the islanders. Both the AEC technician and I kept our knowledge to ourselves because we

feared losing our jobs. I'm greatly relieved now to be passing this revelation along. Perhaps the people of Rongelap

and Utirik will hear of this and avoid eating these poisoned animals.

The moerning of our departure, almost as an afterthought, the people of Rongelap were awarded with one final

gift: a few bags of refined sugar, white flour and white rice. When this was gone, there would be nothing but the radioactive

coconuts, pandanus, papaya, breadfruit and crabs.

This calloused treatment of innocent people shames me. I feel only a very sick attitude could produce

this statement: "The habitation of these people on the island will afford most valuable ecological radiation data on human

beings." (AEC 3-year report on Rongelap and Utirik). This is the same attitude that I experienced personally on

that 1974 voyage.

Self-Support Plan Proposed

The damage that has been done to the health and culture of the people of Rongelap cannot be undone.

But it occurs to me that aid in the form of more handouts can only serve to amplify the feelings of low self-esteem and diminished

pride that we as a society have been responsible for creating in these people's lives.

Therefore, I propose a program of self-help, where the American government can provide tools to these islanders

that will enable them to become self-supporting, proud and independent once again. Here's the plan: The US Department

of Energy (formerly the AEC) should build small refrigeration plants on the radiated islands and provide each island community

with two ferro-cement, motor-sail fishing vessels. This would allow the islanders to catch uncontaminated deep-ocean

fish in the rich off-shore fishing grounds. The catch could then be frozen on the islands for future sale to outside

commercial interests. This operation should be wholly subsidized by the government until the project is paying for itself.

The cost of this operation would be a fraction of the cost of setting off just one A-bomb blast - a small price to pay considereing

the monies spent helping the victims of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. This point is particularly apt when one realizes that

the Japanese were our "enemies" at the time, while the people of Rongelap, Utirik and Bikini are clearly innocent victims

of the American government's caculating disregard.

Only a strong statement from the American people will cause the government to act responsibly in this matter.

Silence and apathy can only serve to perpetuate the death and suffering.

END

| AEC team and staff disembark LCU-26 on Enu Island |

|

| The team flys away to the safety of home and family |

| Bikini Bomb Bunker for A and H-bomb observations |

|

| Bikini Atoll, Enu Island |

| Loading CIA cargo aboard schooner VALKYRIEN, 1968 |

|

| L to R: George, Malcolm, Mike, Stan, Pete, John Hanna |

| CIA electronic surveillance cargo for Pitcairn Is. |

|

| "VALKYRIEN" outbound from Honolulu, 1968 |

|